It took five debates for a moderator to finally ask the Democratic candidates about child care, an issue that hits voters’ hearts, homes and wallets. Why did it take so long — and why aren’t we hearing more about the differences in the candidates’ plans?

As Americans head to the polls in 2020, they’ll be doing so in the midst of a worsening domestic crisis: Child care is so expensive, and in such short supply, that it’s causing families to work less, save less, spend less and even have fewer children than they’d like. The numbers are alarming. While costs are soaring (they rose 2,000% from the 1970s to the 2000s), the supply of care is shrinking (more than half of Americans live in child care deserts). Research finds 7 in 10 families are spending unaffordable rates for child care, but the market isn’t working the way you might expect. Consumer demand for care isn’t driving wages up, in part because families are already so burdened by the costs. In fact, many caregivers tell us they’ve never asked for a raise because they know families are already paying more than they can afford for care.

With pay rates remaining stagnant, many caregivers are leaving the profession because they can’t afford to stay. More than half of the child care workers who remain are in need of public assistance. It’s not surprising, then, that caregivers often leave for another job in search of higher wages and better access to benefits. And while public investment in child care has increased in recent years, the United States still spends well under what most other Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) nations devote to child care and family benefits.

Lack of access to care isn’t just a problem for families. It’s also a competitive disadvantage to American businesses, as compared to their international counterparts: US employers report losing billions each year in lost productivity costs attributed to child care issues. As a result, the effects of our crumbling care infrastructure are being felt by families, companies and the overall economy.

So what are we, as a country, going to do about it?

For the first time, child care is beginning to take center stage as a major campaign issue in American politics, with candidates on both sides of the aisle proposing new legislation aimed at lowering costs, increasing the supply of caregivers, raising caregiver wages and incentivizing businesses to help employees with caregiving needs to remain in the workforce.

The delicate nature of the care economy — with parents paying too much but caregivers being paid too little — means that the details of these plans matter. It’s easy to suggest paying caregivers more — but how do we do that without driving families’ costs even higher? How much public investment can we afford — and who will pay for it? What incentives and innovations will lead to a sustainable system for both families and workers — especially as economists predict that care jobs will play a crucial role in growing our 21st century economy?

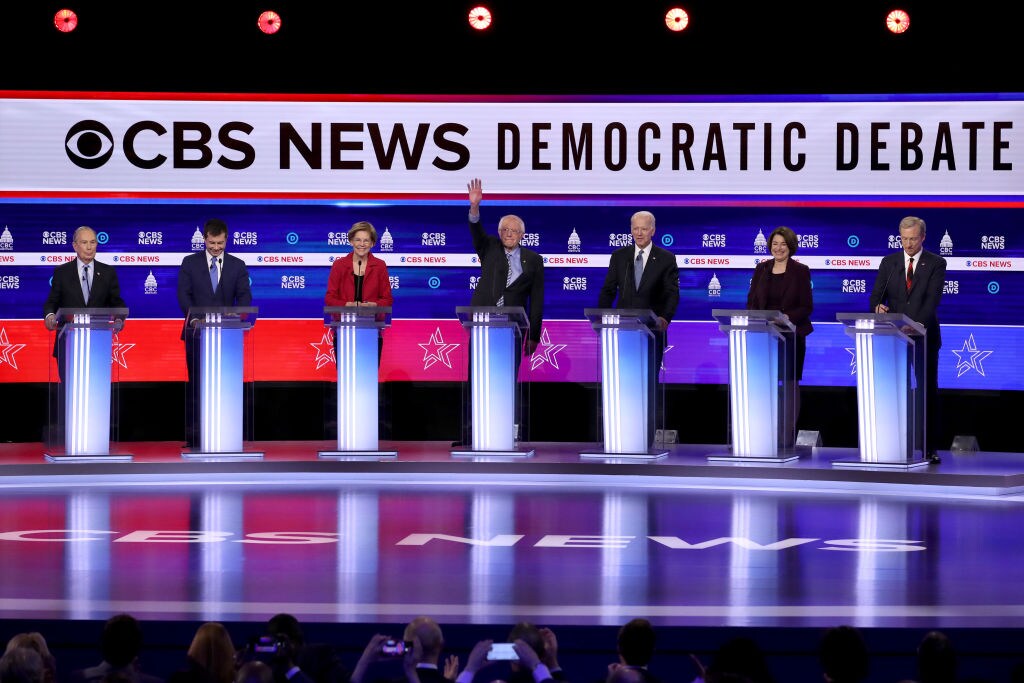

Democratic candidates have demonstrated a wide range of new ideas, from Elizabeth Warren’s universal child care to Andrew Yang’s universal basic income. Other candidates have also signed on to existing plans, such as the Child Care for Working Families Act. We’ll run through them all right here. Let’s dig in.

Elizabeth Warren’s Universal Child Care Plan

Perhaps the best known among the candidates’ plans is Massachusetts Senator Elizabeth Warren’s universal child care plan. Warren’s plan would create a government-funded system to provide free or subsidized care to all Americans, pay care workers at rates comparable to public school teachers and mandate high-quality standards. “In the wealthiest country on the planet,” Warren writes in introducing her plan, “access to affordable and high-quality child care … should be a right, not a privilege reserved for the rich.”

Under Warren’s plan, the federal government would partner with regional providers — meaning cities, states, school districts, nonprofits, tribes and faith-based organizations — to create a locally administered network of child care options available to all families. The plan would cost an estimated $70 billion per year, funded with Warren’s proposed “Ultra-Millionaire Tax,” which would require households to pay an additional 2% tax on every dollar of net worth above $50 million and 6% on every dollar above $1 billion. (Warren says this tax on roughly 70,000 US households would bring in $2.75 trillion over 10 years.)

In return, no family would pay more than 7% of its household income for child care — a ceiling established by the department of HHS to define “affordable” rates for care. Additionally, care would be free for families earning under 200% of the federal poverty level, or about $51,500 in 2019 dollars.

Ambitious and detailed, Warren’s plan has been praised by some — and a team of economists reported the plan could generate $702 billion in economic development over the first 10 years. But it has also been criticized for focusing on a child care infrastructure that isn’t flexible enough for 21st-century families. Proponents of a child care bureaucracy often point to two historic examples: The US enacted a version of universal child care during WWII; and the government currently subsidizes care for low-income families through Head Start. But the woman who ran Head Start and helped create the military’s child care program has warned that neither is a perfect model for a modern universal care system — because they don’t meet the needs of families that work off hours, or fully deliver on providing choices that reflect families’ choices.

Additionally, economists have raised concerns that Warren’s program doesn’t reflect the flexibility needed to support all families — many of whom have schedules that don’t align with in-center child care, or live in places where the population isn’t dense enough to support robust child care centers. In Canada, similar initiatives led to a decline in child care quality, precisely because the ambition to create a system that extended child care for all did not take into account the necessity of training a vast new child care workforce to staff it.

To Warren’s credit, her plan explicitly addresses the challenge of developing a high-quality child care workforce and guaranteeing that early-care educators can earn a living wage. Crucially, the federal government would “pick up a huge chunk of the cost of operating these new high-quality options” under the plan. But the ultimate success of Warren’s plan could hinge on a massive “human infrastructure” project to attract, train and retain a new generation of child care professionals — a project that will likely require an historic partnership between public, private and nonprofit institutions.

Bernie Sanders’ Universal Child Care Plan

Calling the current system “an international embarrassment,” Sanders has introduced a universal child care and early ed plan that would guarantee free child care and pre-K for all children, regardless of their families’ income. The estimated cost is $1.5 trillion over a decade, funded through a wealth tax on those a net worth of over $32 million.

Broadly similar to Warren’s proposal, Sanders would build off existing federal programs. Sanders envisions free universal child care available at least 10 hours a day, operating at times to make care available to parents who work non-traditional hours. The program would be funded by the federal government and administered by state agencies and tribal governments “in cooperation and in collaboration” with public school districts and other local agencies. Quality standards, including minimum wages for workers and mandated child-to-adult ratios, would be established as conditions of the funding.

The Sanders plan also includes universal pre-K for all children starting at age 3, increased resources for supporting children with disabilities, doubling funding for the Maternal, Infant and Early Childhood Home Visiting program for families in at-risk communities, and passing the Universal School Meals Act to provide free meals to every child in child care or pre-K.

To address the supply side, Sanders’ proposal calls for investments in physical and human infrastructure. The plan notes constructing, renovating and rehabbing child care facilities and preschools, while ensuring smaller centers and home-based child care operations can apply for funding to upgrade or renovate their facilities. Sanders would seek to double the number of early childhood educators, from 1.3 million to more than 2.6 million, by guaranteeing a living wage and compensation equal to similarly qualified kindergarten teachers. At the same time, all early childhood workers would be required to have at least a Child Development Associates (CDA) credential, while assistant teachers would be required to have an Associate’s Degree and lead preschool teachers would need a Bachelor’s degree in early childhood education or child development. To help workers pursue the necessary training and credentials, the Sanders plan outlines reasonable phase-in periods, funding union training programs, and stronger protections covering unionizing, collective bargaining, and passage of the Domestic Workers Bill of Rights.

Sanders is also a co-sponsor of the American Family Act and the Child Care for Working Families Act.

The Child Care for Working Families Act

While Warren’s plan may be the splashiest, the most common plan to gain traction among the candidates is the Child Care for Working Families Act (CCWFA). US Sens. Cory Booker D-NJ, Amy Klobuchar D-MN, Bernie Sanders I-VT and Warren are all counted as co-sponsors of the bill, which was first introduced in 2017, by Senators Patty Murray and Maizie Hirono. While Warren’s plan envisions a new child-care bureaucracy, the CCWFA expands on existing programs, such as Head Start. It envisions a sliding scale for cost, based on household income, and it has provisions for increasing the supply of caregivers.

Like Warren’s plan, CCWFA sets a ceiling to control child care costs. Under the plan, no family making less than 150% of state median income would spend more than 7% of household income on child care — the affordability threshold identified by the Department of Health and Human Services. Families earning under 75% of state median income would pay nothing at all.

To bolster the supply of caregivers, the bill would increase workforce training and compensation for child care workers, putting their compensation on par with elementary school teachers. Further, it seeks to improve care in all settings, not just centers — including so-called family, friend and neighbor care that helps fill in the gaps for parents who work nontraditional hours.

How does this get done? The CCWFA would expand two primary major programs, the Child Care and Development Block Grant (CCDBG) and extend Head Start. Currently, the CCDBG is the primary fund through which the federal government funds subsidized child care. This money flows through the states, who in exchange for the grant must guarantee that recipients — families, providers and child care centers — meet certain quality or income thresholds. Typically, families must prove financial need; providers must be paid minimum rates set by the states and centers must be accredited. But today, only about one in six eligible children currently receives subsidies under the CCDBG. While CCDBG currently serves families with income below 85% of state median income and provides care subsidies for 2.1 million children, analysts project about 40 million children would be income-eligible under CCWFA’s broader provisions.

Under CCWFA, the Child Care Block Grants would be increased, and states would be tasked with developing a “tiered and transparent system” for measuring quality of child care providers. Rates would be tied to quality ratings, and families would be charged co-payments on a sliding scale based on their household income levels. Estimates suggest that three out of four children under age 12 would be eligible for assistance under the expanded CCWFA.

By focusing not only on child care costs but also workforce development for caregivers, CCWFA could drive an estimated 2.3 million jobs — some of them for parents who will be able to afford to go back to work and others for workers in child care and early education who will be able to earn a living wage. Of those jobs, the Center for American Progress estimates 1.6 million additional parents would be able to join the labor force, and 700,000 new jobs would be created in child care and early education sectors.

Pete Buttigieg’s Child Care Plan

Before withdrawing from the race, South Bend Mayor Pete Buttigieg introduced a universal child care plan that shared similarities with Warren’s (note the price tag) and the CCWFA (in that it also builds on Head Start). Described as a “historic $700 billion investment in affordable, universal, high-quality, and full-day learning,” Buttigieg’s plan would make early learning and child care free through age 5 for families below the poverty line, between 0 and 3% of household income for families below median income and no more than 7% of household income for any family. It would also initiate a new program to provide cost assistance for working- and middle-class families during after-school and summer hours — periods when working parents with school-aged children struggle to find and afford care. Finally, Buttigieg says he would “invest in workforce development and [additional] compensation for the child care workforce” but has not released details on how or how much.

The Washington Post reports Buttigieg would finance the plan through a combination of a new universal subsidy program and strengthening Head Start programs. Buttigieg says the $700 billion plan would be paid for through reforms to capital gains taxes for the top 1%.

Amy Klobuchar’s Child Care Workforce and Facilities Act

In addition to co-sponsoring the CCWFA, former candidate Sen. Amy Klobuchar introduced the Child Care Workforce and Facilities Act. In recent years, states like Klobuchar’s home of Minnesota have seen a decline in child care capacity — there are fewer child care slots at facilities, and fewer credentialed providers to staff them. The Child Care Workforce and Facilities Act would address this issue head on by funding projects that would increase retention and compensation of quality child care professionals, while also helping child care workers obtain portable, stackable credentials geared toward advancement opportunities. Industry experts suggest that both are crucial for building the nation’s care infrastructure: Child care workers need to be trained, but they also need to be compensated for acquiring higher competencies. Klobuchar’s act would support human infrastructure by providing grants for states to support the education, training and compensation of child care workers. And it would support physical child care infrastructure by funding the construction, renovation or expansion of child care centers in areas facing care shortages.

Mike Bloomberg’s Plans for Program Expansion and Pre-K

Similar to the Child Care for Working Families Act, Bloomberg’s plans to address the cost of child care include expanding the Head Start, CCDBG and CDCTC programs to reach a wider number of children and families. Bloomberg’s website claims he would triple the number of infants and toddlers served by Early Head Start, and reach more 3-to-5-year olds under the expanded Head Start. Further, Bloomberg would increase the number of families who receive CCDBG subsidies and cover more low- and middle-income parents under the Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit. He’d also restore grants for states to reach a goal of universal access to full-day pre-K for 3- and 4-year-olds.

Bloomberg also announced plans to address the quality of child care and compensation for care providers. His proposal includes supporting the creation of a nationally-recognized credential for early childhood professionals and starting an “Apprenticeship Degrees” program to encourage professional development for home-based providers. Bloomberg also notes raising the federal minimum wage to $15/hr would be a nearly $4/hr increase over the average pay for a child care worker. His plan further calls for studying the creation of a refundable tax credit for early childhood educators to boost earnings for teachers and providing grants to states who close the wage gaps between pre-K and Kindergarten teachers.

Finally, Bloomberg’s website says he’d address America’s child care deserts through a “place-based EITC to incentivize child care businesses opening in underserved communities.”

Kamala Harris’s Family Friendly Schools Act

Before withdrawing from the race on December 3, Sen. Kamala Harris — another CCWFA supporter — suggested increasing funding for Head Start and Early Head Start. She also introduced a proposal, the Family Friendly Schools Act, to address the child care gap between kids getting out of school and parents getting home from work. Research has shown that child care gaps (including after-school care responsibilities and school-closing days) cost the economy billions annually in lost worker productivity. So Harris proposed the Family Friendly Schools act in order to pilot a limited program to test more closely aligning school and work schedules. The plan would give 500 schools funding to keep their doors open from 8 a.m. to 6 p.m. — and during professional development days and other times when schools are typically closed while businesses stay open — without forcing teachers to cover those hours.

Michael Bennet’s American Family Act

Sen. Michael Bennet, D-OH, who left the race after a disappointing New Hampshire Primary, is a lead sponsor on the American Family Act, which would attempt to make child care less expensive by expanding the existing Child Tax Credit (CTC) for low- and middle-income families. As the New York Times recently reported, the CTC has a glaring blind spot: “children with the greatest economic need are least likely to benefit” from it. That’s because of the way income taxes work. As researchers found, 35% of children can’t claim the full amount “because their parents earn too little” — including more than half of black Americans and 70% of children with single mothers.

The American Family Act would raise the credit from $2,000 to $3,600 for each child younger than age 6 and $3,000 for children older than 6. More importantly, the proposal would make the credit “fully refundable,” meaning low- and moderate-income families would be eligible to receive the credit’s full value even if they don’t make enough money to pay income taxes. The plan also calls for establishing a program for the credit to be “advanced” — which means, literally, that the tax refund could be advanced to parents throughout the year, putting money in families’ pockets on a monthly or regular basis. The full credit would be available to families filing jointly with incomes up to $180,000 and for $130,000 for unmarried individual filers. Booker, Harris, Klobuchar, Sanders and Warren are all listed as co-sponsors of the bill.

Cory Booker’s Expanded CCWFA + Child Allowance

Before exiting the race,, Booker says he would build on the framework of the CCWFA, including fighting for legislation to “make a sweeping federal investment in high-quality child care to make it affordable for all working families” and supporting increased funding to raise wages of child care workers. Booker’s plans also included creating a “child allowance” for families with children. Believing the current CTC excludes too many children from low-income families, Booker would expand the current CTC and authorize a monthly “allowance” of $300 for families with young kids and $250 for those with children up to age 18. The credit would be indexed to inflation and fully refundable, meaning all eligible families would receive the full amount.

Neither Bennet nor Booker offered specific plans to address the shortage of child care providers through workforce development initiatives.

Andrew Yang’s Freedom Dividend

Andrew Yang, who also dropped out after New Hampshire, baked his plan for addressing the child care crisis into his signature policy proposal, a $1,000 per month “Freedom Dividend” — a form of universal basic income — that would be available to all families. In essence, Yang expected families to defray their costs by using some of that money to pay for child care. Yang also says he would institute universal pre-K by directing the Department of Education to work with states to create a plan. To address the shortage of child care workers, Yang said he’d provide loan forgiveness to education majors who “volunteer at places that provide universal pre-K education.”

Yang also addressed child care, without much detail, in his plan to assist single parents. His proposed investments included tax breaks for child care services and the “creation of responsibility-sharing networks” in which single parents could work with each other to share child care and other responsibilities. It’s unclear whether the tax breaks are new or extensions of existing ones and how the “responsibility sharing” networks would function.

Additional child care plans

While not as robust as other candidates’ plans, former candidates Rep. John Delaney, D-MD, has introduced the Early Learning Act, which would provide guaranteed access to free pre-K for all 4-year-olds, and author and activist Marianne Williamson’s child advocacy proposal mentions affordable child care and universal pre-K.

We haven’t heard specific child care plans from several other Democratic candidates, including former Vice President Joe Biden and billionaire businessman Tom Steyer. Neither former San Antonio mayor and HUD Secretary Julian Castro nor former Massachusetts Governor Deval Patrick revealed child care plans prior to exiting the race.

Child care was also a key issue in the 2016 election, which marked the first time in history both major party candidates had plans for child care and paid leave. We’ve yet to see a significant, national solution for paid leave or child care, but the child tax credit has doubled, from $1,000 to $2,000, under the Trump Administration. As the First Five Year Fund reports, the fiscal 2020 funding bill includes more than $1 billion in increased funding for child care and early learning programs, including a $550 million increase for the Child Care and Development Block Grant program and an additional $550 million for Head Start and Early Head Start.

Whoever the candidate, it’s important to keep our child care crisis front and center as a major campaign issue ahead of the 2020 election. To that end, groups like Moms Rising, SEIU, CAP and Child Care Aware have launched social campaigns using the hashtag #childcare4all. We need innovative, sustainable solutions to this quiet crisis affecting millions of families. And we need to hear it from our candidates for the highest office of the land.